Do mobile phones set citizens free?

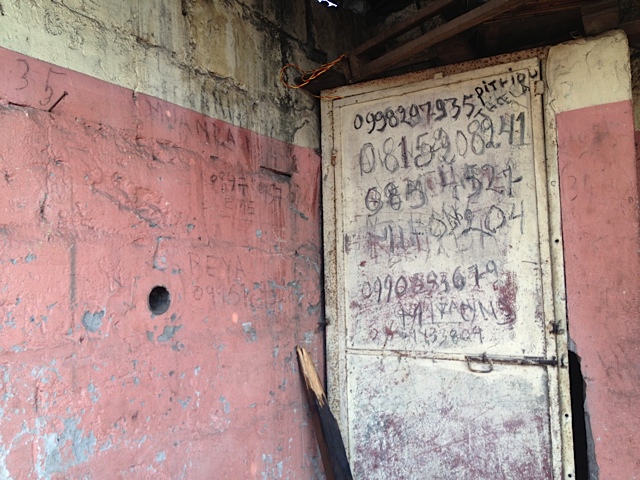

/In postcolonial Kinshasa, citizens use mobile phones (and smartphones) are as tools to deceive the state but also to expose fraud. The Congolese government is also strongly aware of the revolutionary capacities of new media. In 2011, text messages were blocked; and in January 2015, the government shut the Internet for a few weeks, gradually opening up Internet while blocking social media platforms such as Whatsapp, Facebook, Viber and Skype.

It is clear that political change on the continent is not only documented by citizens filming and photographing protest and abuse, but these also feed into the ways in which citizens and the state interact. One should however always be careful to situate these mass-mediated interactions within complex postcolonial histories of governance and political communication.

Read more in the blogpost on the SAPIENS website that discusses research on the embedment of mobile phones, and increasingly smartphones, in processes of political change

The blogpost is a summary of the academic article "‘[Not] talking like a Motorola’: mobile phone practices and politics of masking and unmasking in postcolonial Kinshasa" (Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 2016, 22 (3): 633-652)