Shari Thanjan holds a BA Hons in anthropology from UCT and is a specialist in maternal and child health interventions. For the past six months she has been working as a field assistant with the MediAfrica project.

A cellphone always becomes some sort of a fictional companion in your life. It’s so easy to grow attached to material things, holding you to all your networks and traits of your personality. Your phone becomes a friend in times of need. This piece is about a heartbreaking journey between me, my phone and I. And it leads me to reflect on the research we have been doing on mobile phones and motherhood in Cape Town.

The whole debacle started when I took it to a music festival a few months back. Music festivals are always a risk for all your belongings. You can always lose your most important valuable items, which usually include a bankcard, your favourite items of clothing and of course, your cellphone. On event pages on Facebook, there are always posts of people looking for missing items after the party. Being a “joller” (in South African terms a person who goes out dancing a lot), I have mastered the art of not losing my most important belongings despite partying hard. So, off I go to a music festival with my “I’m a responsible joller who doesn’t lose her things attitude”. Putting my phone in a safe place, keeping my bags closed tightly and always on my back to avoid losing my phone. Coming home on the Friday night, I was extremely chuffed with myself for not losing anything. The next morning I went for a breakfast with my friend, happy as a hummingbird. This happiness was cut short, as my phone suddenly fell on the ground whilst getting out of the car to come home. In shock I quickly picked it up to check if the screen cracked. A sigh of relief, not one crack! Then, as I turned it on, the screen remained blank, black, dead. I immediately started thinking of things I could do to fix it, thinking maybe I could put it on the charger and then it will come back to life. My mind started racing with all sorts of silly ideas. I felt so stupid, as all my “responsible” actions, the night before, putting my phone in a safe place, keeping my bags closed tightly and always on my back to avoid losing my phone, were apparently for nothing. So, there I was in an ironic situation, annoyed with myself and the universe.

Firstly, and most importantly,the phone held the ties to my boyfriends. My one boyfriend, who is sort of an ex but still a friend ( its complicated) asked me to behave while I was at the music festival and report to him, where I was and how I was doing, as he needed to know(apparently) that I was safe. Then, a boy I had been crushing on for years, was at the festival and I had drunk-texted him at three am confessing my dear feelings and was still awaiting his response that Saturday morning, but alas, my dear phone broke .Until today, I don’t know what his reply was! I always wonder if a potential and blossoming romance was cut short, by my broken phone. Obviously, it was not meant to be, but a girl can dream sometimes.

Secondly, my broken relationship with my phone affected my friendships. Of course at a festival in a city where you have many friends, you want to meet with them for pre-festival fun. Now I could not contact any of my buddies, getting some disappointed moans from friends when I saw them later that evening.

Further, without my phone I worried about my safety, potentially getting lost, and not having the ability to contact my people, or uber home. So my whole social circle and interactions, which are particularly important in the light of a music festival weekend, was all lost within that moment of my phone breaking.

Part of going for a good party these days is capturing all of the music, videos, pictures, the venue and gorgeous selfies on your cellphone. Just for keeps or to share on Instagram, WhatsApp or Facebook, to show the world what a marvellous time you had . I worked hard on the Friday night taking as many cute selfies and beautiful pictures as I could, only to have it all lost. It tried to borrow my friends phone, which is difficult as their cameras work differently and sometimes their memory gets full and stuff. Eee, I guess one should just live in the moment, right? Well, now I didn’t have a choice!

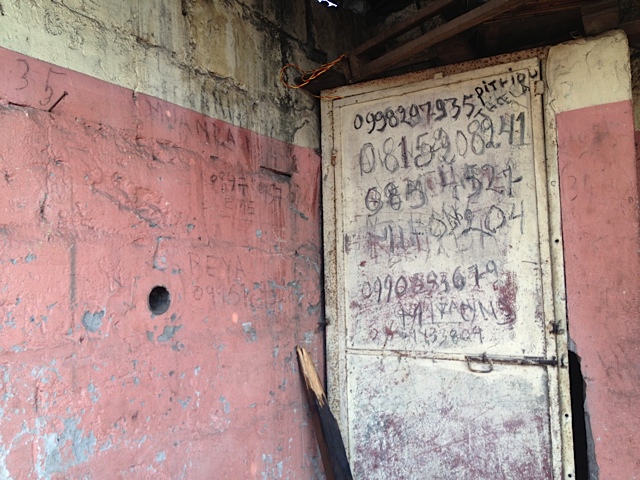

Without my phone my personal life seemed to be in shambles. But worse, my job as a research assistant was set back. All of my research participants contact details were saved on my phone as well, and now I wondered how to even get in touch with them. Believe me, some of them were hard to come by. And what about doing interviews? All my recordings of interviews were done on my phone. We had also collected something we called media diaries from participants, which is a documentary of their everyday lives recorded on their phones. Though we had wisely made backups, I could not view this material on my phone any longer. How could I do my work with no phone?

It was so heart breaking. I was so upset and there and then, with my broken phone. A material object I owned had the ability to break my heart. There wasn’t much sentiment attached to my phone as an artefact, but more emotion attached to the services it could provide me with- ranging from the camera to the social ties and work - it was all gone.

Yet, in the midst of all this agony there was a light. Through doing many interviews in poverty stricken areas in Cape Town, I soon came to realize that my agony was shallow, and honestly quite silly and I should not have been so upset. Many of the mothers we spoke to did not have smartphones, or even phones. Their reason for this was its unaffordability as the prices of data in South Africa are unaffordable to most, but also more disconcerting was: Some were afraid to be robbed, if they had a (nice) phone, and some did not have a phone because it had already been stolen. While I fret and worry about Facebook posts, many people had access to Facebook as part of a data saving network plan, whereby one couldn’t see pictures and videos, only writing. Many of our research participants hardly went on social networks. Some avoided it purposefully, to avoid all the social drama attached to networks.

The moms we worked with who did have a phone often bought a WhatsApp bundle for R12.50, which lasted them the whole month, and did not include downloading of pictures and videos. Many survived with just this as their main form of communication with partners, family and friends. While sitting in the clinics, trying to get moms to register on MomConnect, many of the moms were not even interested in their phones, or had any idea how to use it. This happened with moms of all ages. I had to assist most people I met with the whole procedure.

My time in the field and comparison with my own phone really made me realize, that even though statistic screams that South Africa has 100% mobile penetration, it is not even so. South Africa is a majority poor country. Yet, although there are many mobile interventions deriving from policy, pushed into South African programmes, it seems that end user was not considered, basically, the people of South Africa. In almost every interview I did, or people I met throughout fieldwork could not afford the phones imagined for the mobile interventions.

Going back to my drama, my fieldwork really showed me that a phone is not everything, and one can actually live a happy content life without it. The participants in the research showed me this, and helped me, well, get over my self and my phone.